I’m excited to announce a huge milestone in our work at BranchLab because it proves out a hypothesis I had when I joined: we have now shown that capturing the clinical heterogeneity in our outcomes lets us better predict them from demographic data. In my past work in drug-related R&D, we talked about heterogeneity all the time; we were always looking for patient subgroups that might have better drug efficacy or different mechanisms of disease. This is because, as I previously wrote, it’s a proven paradigm in precision medicine. At BranchLab, we’ve always used demographic data to predict who might have or might be likely to develop a condition. Using patient subgroups in this context is not a proven paradigm, and so even as I advocated for testing this hypothesis, I was unsure whether it would work. Here I’ll share more about the obstacles we faced and overcame in demonstrating that we get better predictions of outcomes in a metabolic disease by accounting for this clinical heterogeneity.

Our PATH Stack trains transformer models to understand clinical journey data and then clusters these clinical journeys to find these subgroups of people. This pits us against a classic data science conundrum; you can always cluster data, but it doesn’t matter if the clusters aren’t meaningful. I’ve often seen wayward data scientists make this mistake, for example delivering clusters for use in clinical trials that actually weren’t meaningful and had poor performance in predicting outcomes, or clusters from cellular data that claimed to find a new cell type, but it was really an artifact. Finding meaningful and relevant clusters is hard, but necessary in order to fully test this hypothesis.

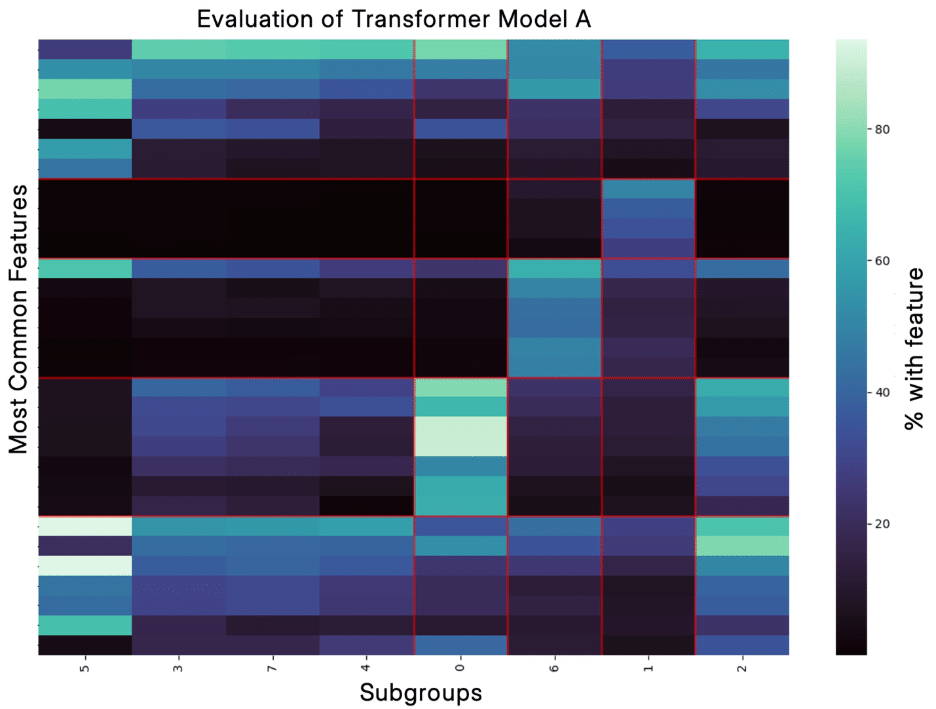

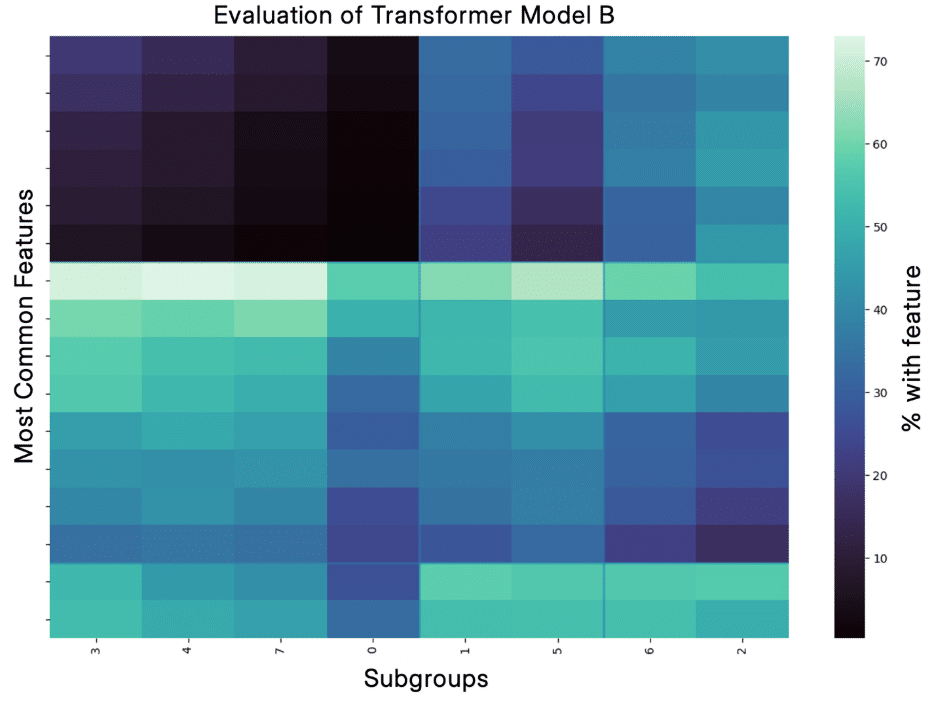

Because of this, one important piece of our PATH Stack is evaluating how well the subgroups we identify with different transformer models capture the real clinical heterogeneity. We have a robust and complex evaluation pipeline to do this, and we’ve seen that models can perform well on traditional metrics without having captured clinical heterogeneity. Below, you can see two examples of one of our evaluation pipeline outputs from work on a metabolic disease. For Transformer Model A, you see that the subgroups are quite different; there is high contrast as you look across the columns, and in fact, statistical testing shows that each subgroup has features that are enriched compared to the other subgroups. In contrast, for Transformer Model B, you can see almost no difference between the subgroups in the second plot, there are fewer features that meet our selection criteria because they are less unique, and there are no significant features.

I believe this ability of the PATH Stack to identify real clinical heterogeneity is critical not only for interpretability but also improves performance in our predictive PANDA Stack, which uses demographic data to predict a health outcome. Supporting this, the model in the top figure improves PANDA performance (measured by ROC AUC) as compared to ignoring the heterogeneity and only predicting the metabolic disease outcome by over 10%.

I am thrilled by this result and look forward to sharing additional results in the future as we continue to improve our ability to create audiences that over-index for nuanced groups of people and are predictive of future diagnoses.